The Trojan war and the Trojan horse are omnipresent in the world of epic. In Aeneid book 2, we witness via a flashback the famous scene where the Trojans take into their city a giant wooden horse in which the Greek soldiers were hidden, and that night the Greeks jump out and ambush their foe; in Odyssey book 4, Menelaus at his court in Sparta tells this story to Odysseus’ son Telemachus; and the whole of the Iliad is framed around the Trojan war, even though the epic stops just short of the horse episode itself. Such a compelling and curious vignette repeats in myth, and is one of the most iconic images from the ancient world that we might recognise today – but was it real?

This curious vase from the island of Mykonos might make us think twice. Here we have a relief pithos which dates from the start of the seventh century BC, and we know that it was used as a burial urn because human bones were found within the pot. All over the body of the pithos we see small scenes of warriors fighting one another, framed within individual squares called metopes. The most iconic scene, however, is on the neck of the vessel: a scene which shows a giant (wooden?) horse. Seven armoured men are peeping through little windows cut into the body, and seven armoured men have already descended from the horse and are ready for battle. No prizes for guessing, this looks just like the scene which Homer and Virgil described.

The seventh century date when this pot was made also marks the time during which the Homeric epics were first written down. This is not to say that the artist of the Mykonas vase was directly inspired by the poet of the Iliad or vice versa, rather it is interesting to see that similar sorts of ideas were circulating at the same time in both the visual and the literary spheres. Stories about battles and the depiction of heroes each tell us about the social background to Homer’s world. This was a time during which aristocrats and elites competed for status and honour, and one way in which they could achieve this was through exploits on the battlefield. This wider context can help us to understand why stories of this nature made their way into literature and art – and the seventh century BC only marks the beginning of this phenomenon: images of war and heroic deeds dominated Greek art from this time onwards.

So, over to you – do you believe that there was ever really a Trojan horse?

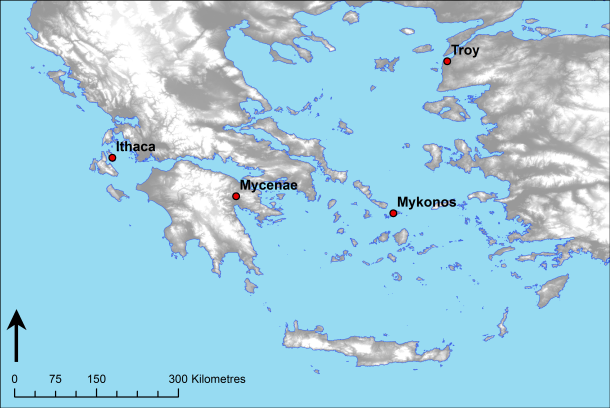

The island of Mykonos, side by side with Troy, Mycenae (King Agamemnon’s home) and Ithaca (Odysseus’ home).

This blog post has been written in order to support the content of the OCR Classical Civilisation GCSE topic ‘The Homeric World’ and the OCR Classical Civilisation A level module ‘The World of the Hero’.

Further reading:

Ervin, M. 1963. ‘A Relief Pithos from Mykonos’ AD 18: 37-75.

http://ir.lib.uth.gr/bitstream/handle/11615/14818/article.pdf?sequence=1

Langdon, S. 2008. Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 BCE. Cambridge.

Snodgrass, A. 1998. Homer and the Arists: Text and Picture in Early Greek Art. Cambridge.

Wood, M. 1985. ‘In Search of the Trojan War’, BBC TV Documentary. [especially episode six]

‘The seventh century date when this pot was made also marks the time during which the Homeric epics were first written down. ‘ yep but that doesn’t necessarily tell us about teh thirteenth century

Exactly – original oral composition of the poem earlier and looks back to an even earlier (bronze?) age. But this is the earliest we can trace the written and visual records.

yes

yes

Pingback: Island hopping around Greece, volume 1: Mykonos, Delos, and Tinos | res gerendae